Understanding your characters’ motivation is key to developing strong characters.

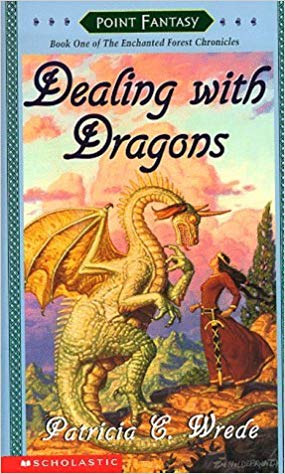

One of my favorite examples comes from one of my favorite childhood books, Princess Cimorene from “Dealing with Dragons.” She feels trapped in her life as a princess and is about to married off to a ridiculous prince, so she volunteers to be a “captive” princess for a dragon and ends up having all sorts of adventures while fending off knights who keep trying to “rescue” her.

One of my favorite examples comes from one of my favorite childhood books, Princess Cimorene from “Dealing with Dragons.” She feels trapped in her life as a princess and is about to married off to a ridiculous prince, so she volunteers to be a “captive” princess for a dragon and ends up having all sorts of adventures while fending off knights who keep trying to “rescue” her.

Character motivation is the driving force behind what characters do and the choices they make. Motivations are based on needs. These are deep-seated needs that affect every aspect of their lives and psyches. They may be internal (psychological or existential) or external (survival).

Motivation spurs the character (and story) to keep moving, growing, and developing over time. Whatever need they have needs to be fulfilled, and making choices or taking action helps get them closer to that fulfillment. The steps the character takes to fulfill a need become major and minor plot points.

Motivation also makes a character more relatable. Every human has needs. Even though our individual needs vary, we all understand that desire to seek for something else, move forward, or find a better situation. Starting with a universal need helps reach a wide range of readers. That motivation can then be tailored to the character and story and narrowed down into something unique without losing reader interest.

Motivation provides characterization. It tells the reader something important about that character, such as how they were raised/treated, what cultural norms shaped their morals or values, what expectations they have for themselves or others, etc. Motivation also reveals important truths about character roles and how they fit in to the story.

Every character needs a motivation, even side characters and antagonists. Side characters don’t need to be developed as deeply, and may only have a general need or motivation, but having something that drives them makes them more realistic. Antagonists act in frustrating or despicable ways for a reason. They are also trying to fulfill a motivation, often a self-serving or misguided one, but they must have a goal that directs their character arc in order to be realistic and engaging.

Motivations must be realistic. That doesn’t mean their end goal is realistic, but it has to be something a reader can believe the character is truly motivated by. Illogical, weak, or lazy motivations make characters aggravating and unrelatable. Motivations can easily be deluded, irrational, misguided, or even malicious. It’s important that the motivation comes from a base need that readers can understand, even if they don’t agree with or like it.

Goals and motivations are not the same thing. Motivation can lead to goals and steps that need to be taken. Goals are the end result, the fulfillment of a motivation. Motivation is what drives the character to keep moving toward a goal even when it’s incredibly difficult.

Characters can have multiple, and even conflicting, motivations. Humans are not rational creatures most of the time. We want things that keep us from reaching other goals all the time. We want things we know we can’t have. We self-sabotage. We want two things that can’t coexist together. Don’t shy away from making your character complex…within reason.

Writing to market also means knowing general audience expectations, likes, and dislikes. Generally, readers don’t have a strong preference for standalones or series, a plot that moves quickly and well-developed characters keeps readers from putting down a book, blurbs and book covers that don’t accurately portray a book upset readers, readers prefer to interact with authors on Facebook more than other platforms, most readers do want to interact with authors, and readers pay attention to reviews.

Writing to market also means knowing general audience expectations, likes, and dislikes. Generally, readers don’t have a strong preference for standalones or series, a plot that moves quickly and well-developed characters keeps readers from putting down a book, blurbs and book covers that don’t accurately portray a book upset readers, readers prefer to interact with authors on Facebook more than other platforms, most readers do want to interact with authors, and readers pay attention to reviews.

Sweet

Sweet No explicit sensuality, kissing and touching is okay but physical descriptions are limited to general terms or are only implied. Physical acts should be focused on the emotional elements rather than explicit description. Off-screen sex is alluded to and left to the reader’s imagination. Think PG-rated movie.

No explicit sensuality, kissing and touching is okay but physical descriptions are limited to general terms or are only implied. Physical acts should be focused on the emotional elements rather than explicit description. Off-screen sex is alluded to and left to the reader’s imagination. Think PG-rated movie. Moderate explicit content and sensuality. Sex is described, but not in graphic detail. The emphasis stays on the “lovemaking” and emotions, not the act. Euphemisms are more common and many details are left to the reader’s imagination. Sexual tension is used throughout, with more touching and some undressing involved, and there are usually only one or two sexual scenes in the whole book. Think PG-13 rated movie.

Moderate explicit content and sensuality. Sex is described, but not in graphic detail. The emphasis stays on the “lovemaking” and emotions, not the act. Euphemisms are more common and many details are left to the reader’s imagination. Sexual tension is used throughout, with more touching and some undressing involved, and there are usually only one or two sexual scenes in the whole book. Think PG-13 rated movie. Very explicit sensuality and a deeper focus on sexual feelings, desire, and physical sensations. Sex scenes are longer and may have 2-3 in the book. Character thoughts are focused more on sexual urges and desires and sex is graphically described with specific body part words used and strong euphamisms. There may be light exploration of less-traditional sexual activities. The emotional aspect of sex is still important and should be balanced with the physical sensations. Sex scenes should further the story, not overtake it. Think R-rated movie.

Very explicit sensuality and a deeper focus on sexual feelings, desire, and physical sensations. Sex scenes are longer and may have 2-3 in the book. Character thoughts are focused more on sexual urges and desires and sex is graphically described with specific body part words used and strong euphamisms. There may be light exploration of less-traditional sexual activities. The emotional aspect of sex is still important and should be balanced with the physical sensations. Sex scenes should further the story, not overtake it. Think R-rated movie. Extremely explicit sensuality and descriptions with a strong focus on sexual thoughts, desires, and needs. Sex may be the primary focus of the story, but it still has a full-arc storyline and strong emotional elements. Sex often includes non-traditional elements such as light BDSM, use of sex toys, ménage or other forms of “kink.” Profanity is more common and graphic language is used in descriptions. There are usually multiple sex scenes throughout the book. These stories can’t be told adequately without the sexual content. Think NC-17-rated movies.

Extremely explicit sensuality and descriptions with a strong focus on sexual thoughts, desires, and needs. Sex may be the primary focus of the story, but it still has a full-arc storyline and strong emotional elements. Sex often includes non-traditional elements such as light BDSM, use of sex toys, ménage or other forms of “kink.” Profanity is more common and graphic language is used in descriptions. There are usually multiple sex scenes throughout the book. These stories can’t be told adequately without the sexual content. Think NC-17-rated movies.

Hero: Predominantly “good”, struggles against evil to restore balance, justice, etc. (Luke Skywalker)

Hero: Predominantly “good”, struggles against evil to restore balance, justice, etc. (Luke Skywalker) Plot: the main events of a play, novel, movie, or similar work, devised and presented by the writer as an interrelated sequence.

Plot: the main events of a play, novel, movie, or similar work, devised and presented by the writer as an interrelated sequence. Plot should guide the reader through a story, providing pertinent information and raising questions that will keep them interested. Plotting gives the writer the chance to recognize important questions and provide the answers in a satisfying and compelling way. This applies to both pantsers and outliners, though it may progress in different ways.

Plot should guide the reader through a story, providing pertinent information and raising questions that will keep them interested. Plotting gives the writer the chance to recognize important questions and provide the answers in a satisfying and compelling way. This applies to both pantsers and outliners, though it may progress in different ways. Consider the questions asked about the egg-buying character. Eggs are most likely not the real conflict. In attempting to answer some of the questions about this character, the possibilities are endless.

Consider the questions asked about the egg-buying character. Eggs are most likely not the real conflict. In attempting to answer some of the questions about this character, the possibilities are endless. One of the key elements in writing strong female characters (and this applies to writing strong characters of any gender), is understanding the difference between behaviors and personality traits. Behaviors are things a character does (what we do), while a personality trait is how a character behaves, thinks, and feels (what we are). Personality traits are difficult or impossible to alter, while behaviors can be changed.

One of the key elements in writing strong female characters (and this applies to writing strong characters of any gender), is understanding the difference between behaviors and personality traits. Behaviors are things a character does (what we do), while a personality trait is how a character behaves, thinks, and feels (what we are). Personality traits are difficult or impossible to alter, while behaviors can be changed. Fighting: perhaps the character grew up in a rough home life and had to defend herself from a family member, bully, gangs, etc. Perhaps she was a victim and learned to fight for protection.

Fighting: perhaps the character grew up in a rough home life and had to defend herself from a family member, bully, gangs, etc. Perhaps she was a victim and learned to fight for protection.

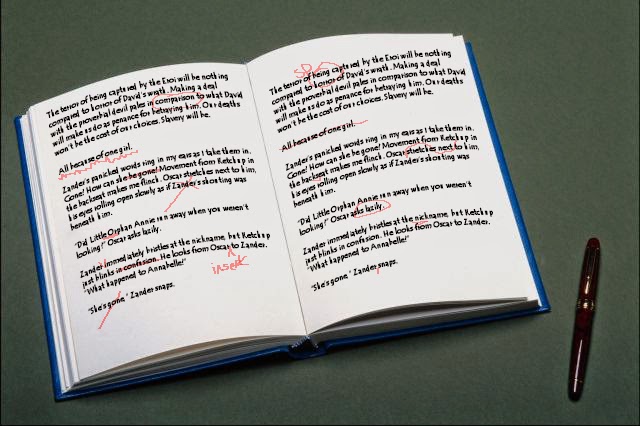

Foretelling: Had I known the darkness forming in my mind weren’t my own thoughts, I would have attempted to defend myself.

Foretelling: Had I known the darkness forming in my mind weren’t my own thoughts, I would have attempted to defend myself.