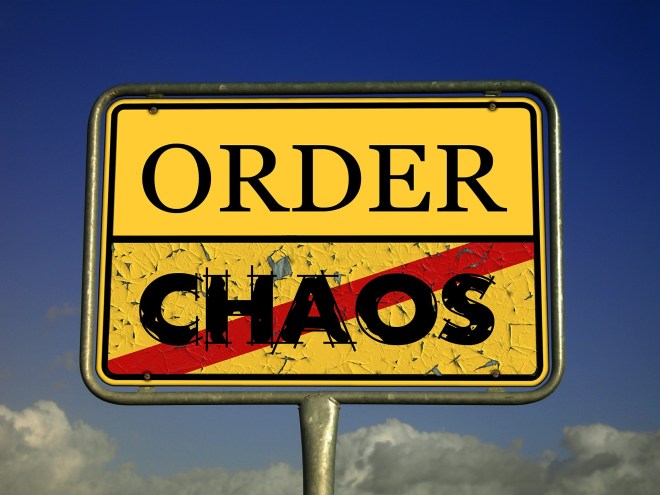

Foreshadowing is a great way to create anticipation in the reader, but it can easily be confused for foretelling.

Foretelling is to predict or tell the future before it occurs (a prophecy), while foreshadowing is to presage or suggest something in advance. It’s a subtle difference, but it makes a big difference in a story.

Foretelling is direct and explicitly tells the reader what will occur. While this is more common in young children’s literature, it’s usually not the best choice for other fiction forms. Foretelling takes the discovery away from the reader. It doesn’t make them work to understand the hint and can spoil the mystery or anticipation.

Foreshadowing involves the reader more full yin the story by asking them to put in the effort to not only pick up on the hints given, but remember them and fit them into the rest of the information and events. Readers feel more invested in the story when they feel like they are participating in it.

What do these two look like in fiction? Here are a few examples:

Foretelling: Had I known the darkness forming in my mind weren’t my own thoughts, I would have attempted to defend myself.

Foretelling: Had I known the darkness forming in my mind weren’t my own thoughts, I would have attempted to defend myself.

Foreshadowing: These thoughts feel so foreign, but I can’t deny they’re in my mind, constantly nudging and pushing me to see Alex’s words and actions more clearly.

In the first example, the reader is told the dark thoughts come from an external source and the character has lost control of their own mind. This asks the reader to do no work and requires them to simply wait for the character to realize the manipulation or see how it all shakes out. Reader investment and participation is very low.

In the second example, there is a hint that the dark thoughts aren’t usual for the character, but is contrasted by the hint that the change might be needed…if Alex’s words and actions truly are harmful. This creates anticipation because the reader doesn’t know for sure whether the character is being manipulated or is starting to see things more clearly. This creates a sense of wariness and anticipation to figure out the truth. Readers will pay more attention to find more clues and figure out the mystery. Reader engagement and investment is high.